Over the past year, environmental activists involved with groups such as Safe Ag Safe Schools and Safe Strawberry Monterey County Working Group, have taken up the crusade to ban pesticides in California using missing and incomplete science.

One such member, Carole Erickson, a retired and somewhat active Public Health Nurse/Educator, promoted here discredited study to the Visalia Times-Delta in July 2017 who was duped into writing:

Scientists from the United States Environmental Protection Agency found that exposure from the pesticide’s [chlorpyrifos] residue on fruits and vegetables to children ages 1 to 2 who eat them is 14,000 percent higher than considered safe.

A quick Google search of this claim reveals that Erickson failed to mention that the United States Science Advisory Panel for the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) ultimately rejected those exposure scenarios, invalidating her claims.

In this 2016 risk assessment, the EPA found the earlier data was based off a flawed Columbia Study that has been thoroughly discredited by subsequent and more in-depth studies by the University of California, Berkeley and Mount Sinai Hospital.

Chlorpyrifos is a pesticide that has been used since 1965 to kill a number of pests including soil-borne insects and worms. Chlorpyrifos is used on soybeans, fruit and nut trees, Brussels sprouts, cranberries, broccoli, cauliflower, and other row crops.

Non-agricultural uses include applications to golf courses, turf, green houses, and non-structural wood treatments such as utility poles and fence posts. It is also registered for use as a mosquito adulticide, and for use in roach and ant bait stations contained in child resistant packaging.

Without chlorpyrifos, our fruit and vegetables would look like:

Multiply that by the billions of pounds of fresh food California produces each year to feed our state, nation and world.

What activists like Erickson ignore is that the United States is among nearly 100 countries that have registered chlorpyrifos for use by farmers.

In fact, the more than 4,000 regulatory guideline studies are subjected to critical evaluation by regulatory authorities in the estimated 100 countries where the product is currently registered and legally approved for use.

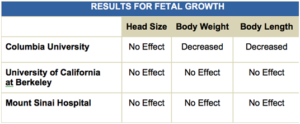

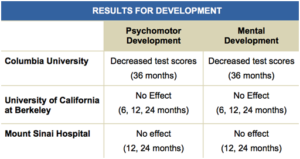

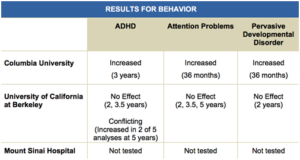

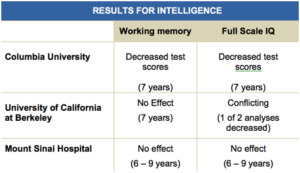

Here is how the discredited Columbia University matches up with the UC Berkeley and Mount Sinai Hospital studies mentioned above:

Note: Berkeley and Mount Sinai researchers noted no statistically significant decrease in fetal growth outcomes associated with exposures based on the chlorpyrifos breakdown product TCPy. 2, 6, 7

Note: Berkeley and Mount Sinai researchers found no statistically significant decrease in development with exposures based on the chlorpyrifos breakdown product TCPy or DEP. 3, 8, 9

Note: Berkeley researchers found no consistent increase in adverse behavior with exposures based on the chlorpyrifos breakdown product TCPy or DEP. 3, 8, 10

Note: Berkeley and Mount Sinai researchers found no consistent decrease in intelligence scores with exposures based on the organophosphate breakdown product DEP. The breakdown product TCPy was not analyzed. 4, 9, 11

REFERENCES

- Visalia Times Delta: Tulare County Residents Advocate Banning a Harmful Pesticide: http://www.visaliatimesdelta.com/story/news/2017/07/16/tulare-county-residents-advocate-banning-harmful-pesticide/475859001/

- Whyatt, R.M., et al., Prenatal insecticide exposures and birth weight and length among an urban minority cohort. Environ Health Perspect, 2004. 112(10):1125-32.

- Rauh, V.A., et al., Impact of prenatal chlorpyrifos exposure on neurodevelopment in the first 3 years of life among inner-city children. Pediatrics, 2006. 118(6):e1845-59.

- Rauh, V., et al., Seven-year neurodevelopmental scores and prenatal exposure to chlorpyrifos, a common agricultural pesticide. Environ Health Perspect, 2011. 119(8):1196-201.

- Rauh, V.A., et al., Brain anomalies in children exposed prenatally to a common organophosphate pesticide. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA, April 30, 2012. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1203396109.

- Berkowitz, G., et al., In Utero Pesticide Exposure, Maternal Paraoxonase Activity, and Head Circumference. Environ Health Persp, 2004. 112(3):388-391.

- Eskenazi, B., et al., Association of in utero organophosphate pesticide exposure and fetal growth and length of gestation in an agricultural population. Environ Health Perspect, 2004. 112(10):1116-24.

- Eskenazi, B., et al., Organophosphate pesticide exposure and neurodevelopment in young Mexican-American children. Environ Health Perspect, 2007. 115(5):792-798.

- Engel, S.M., et al., Prenatal exposure to organophosphates, paraoxonase 1, and cognitive development in childhood. Environ Health Perspect, 2011. 119(8):1182-1188.

- Marks, A.R., et al., Organophosphate pesticide exposure and attention in young Mexican-American children: the CHAMACOS study. Environ Health Perspect, 2010. 118(12): 1768-1774.

- Bouchard, M.F., et al., Prenatal Exposure to Organophosphate Pesticides and IQ in 7-Year Old Children. Environ Health Perspect, 2011. 119:1189-1195.